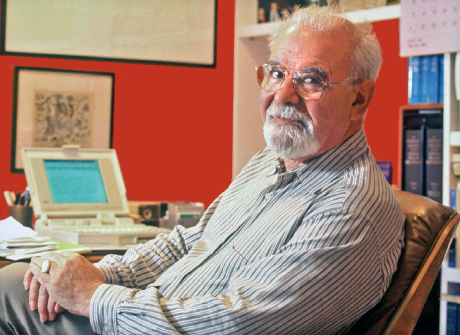

Remembering Rakoff

by Greg Dubord, MD

My introduction to “perennial psychotherapy” was with Vivian Rakoff, MD, CM, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Rakoff was known as un homme de lettres at UofT. Some said he was a flâneur who had popped in through a time portal, likely with a high hat and walking stick, and clearly from a more refined and literate era.

I had the privilege of having Dr Rakoff as my psychotherapy supervisor for three years in the mid-1990s. We always met in the library of his home in Rosedale, which to me resembled the British Museum’s magical Enlightenment Gallery. In addition to countless leather-bound books, he possessed an impressive collection of curiosities from his travels around the world. No mysterious artefact would have seemed out of place in Rakoff’s library. Tibetan tantric tonkas, hairy Haida masks, ceremonial ayahuasca bowls, Fijian cannibal forks, winged Greek penises, and Zulu leather shields all would have been at home there.

At the time I was completely enthralled with cognitive behavior therapy. So when Rakoff referred to my beloved CBT as, “old wine in new bottles”, I should have prepared myself for what was to come.

My naïve expectation was that our case discussions would focus on the minutiae of diagnoses, the subtleties of general psychotherapy, and the finer points of medication management—along with some tidbits from philosophy, religion, and literature tossed in to round things out. But the reality was entirely the reverse. Every one of our thirty-three hour-long tutoring sessions began with the briefest discussion of standard psychiatry before rapidly moving into the liberal arts. For example:

- The case of my patient grieving her teenage daughter began with a quick critique of Kübler-Ross, but ended with Plutarch’s Consolatio ad Uxorem (611AD)—the remarkably soothing letter the Greek philosopher wrote to comfort his wife upon the death of their daughter Timoxena.

- The case of my chronic pain patient began with a short discussion of PET imaging and opiate receptors, but ended with Rakoff’s eloquent interpretations of the surrealist art of Frida Kahlo—the long-suffering Mexican artist who produced haunting images of pain and death.

- The case of my patient who’d been defrauded in an overseas venture began with an examination of DSM’s psychopathy criteria, but ended with a review of Baltasar Gracián’s The Art of Worldly Wisdom (1647)—the Spanish Jesuit’s compendium of 300 maxims.

- The case of my domestically abused patient began with a review of evolutionary psychiatry “mate poaching” literature, but ended with an animated and pacing Rakoff reading from Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879)—the Norwegian playwright’s commentary on female oppression.

- The case of my alcoholic litigation lawyer patient began with a short analysis of genetic studies, but ended with an interpretation of the art of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec—the post-impressionist who celebrated the Parisian bohemian lifestyle (and who succumbed to alcoholism and syphilis at age 36).

Rakoff helped me put modern psychiatry into a much larger historical context. I came to view psychiatry as “the clinical application of wisdom” as much as applied neuroscience—and most of modern psychotherapy as rebottled old wine.

At the end of every tutoring session I headed out with my ears down and my tail between my legs for the University of Toronto library or the now-defunct “World’s Biggest Bookstore”—and to the liberal arts sections in particular.

Sadly, on October 1, 2020, Rakoff again stumbled upon the time portal that had originally gifted him to us. Some say he brushed up against that curious humming orb on the seventh shelf next to the long-lost miniature of Pan and the Goat from Naples’ Secret Museum—but we may never know for sure.

I very much hope to see my beloved mentor again. Perhaps he’ll be wearing a high hat and swinging a walking stick while strolling the streets of le quartier Montmartre, or reading Wittgenstein under the Kunsthistorisches Museum dome, or examining a new character in Bosch’s “Garden” at the Prado—or maybe bundled in a hanten and sipping miso while watching the snow falling softly on the Ryoan-ji boulders in Kyoto.

Vivian Rakoff was a profound and irreplaceable influence in my life. I wish him deep peace.

Greg Dubord, MD

CME Director

CBT Canada